I am currently participating in a discussion with the ISTE LinkedIn Group. The discussion started out with asking for ideas for integrating Google Maps into Learning Activities; however, a side discussion lead to a conversation regarding designing learning activities/courses. The following is my response, which references my previous post/presentation Course Design for Learning.

All too often I've seen Education faculty require their students to create lesson plans and/or activities out of context. However, when the students get into the "real world" they will need to consider a lot more. I like to have my students essentially develop a case study scenario in which they define the state standards and learner characteristics for their classroom--then build a thematic unit plan (rather than a series of individual learning activities) so they see how to integrate technology (and multiple disciplines) throughout the unit.

I'm a great believer in metacognition--understanding WHY you do something. Therefore, I see the course design process as a reflective process. What I try to get my students (and faculty) to understand is that your goals and objectives drive the activities and ultimately assessment. You have to think through which concepts need to be "covered" and what you want the students to be able to do/understand first. That means you have to know what your state/county/district wants you to teach as well as what your students know/don't know. (The ISTE standards (NETS) are another consideration.) Knowing your students is as important as knowing your objectives. You also have to consider your learning environment--what kinds of technology do your students have access to--at school and at home? What kind of support will they need--you provide? Then you need to consider the teaching and learning process--teacher-centered/student-centered or a combination. Teachers need to have a toolbox of instructional strategies that fit their teaching philosophy and think about the materials/resources that can support those strategies (be they low tech or high tech or no tech).

NOTE: Course design is an iterative--not linear--process. Although I listed assessment last, it actually needs to be considered throughout the process (formative vs. summative).

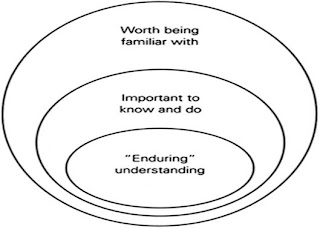

The following related Chronicle of Higher Education article was recently shared on LinkedIn Updates: Planning a Class with Backward Design Mark Sample referenced the book, Understanding by Design, by Grant Wiggins and Jay McTigh. Wiggins and McTigh call the process of designing courses around learning goals “the backward design process.” They offered a three-stage diagram of the backward design process:

- Identify desired results (What should students know, understand, and be able to do? What is worthy of understanding? What enduring understandings are desired?

- Determine Acceptable Evidence (How will we know if students have achieved the desired results and met the standards? What will we accept as evidence of student understanding and proficiency?)

- Plan Learning Experiences (With clearly identified results (enduring understandings) and appropriate evidence of understanding in mind, educators can now plan instructional activities.)

ALPS, Active Learning Practice for Schools, developed by the Harvard Graduate School of Education and Project Zero defines the enduring understandings as Throughlines. Throughlines are overarching describe the most important understandings that students should develop during an entire course. The understanding goals for particular units should be closely related to

one or more of the throughlines of the course.

The enduring understandings, the throughlines, should be the target for developing our course/unit/learning activity. In developing the enduring understanding goals, ask yourself, "When my students leave my class at the end of the course, what are the most

important things I want them to take away with them?" You may have to review several learning units to find common themes or skills/knowledge that seem to resurface each time you teach. Sometimes it is easier to phrase the overarching goals as questions rather than statements.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thanks for your comments.